excerpts from my unsworn declaration - part two

tales from tax court - episode two

there are only two categories of taxes under the constitution and the requirements for each type of tax are explicit:

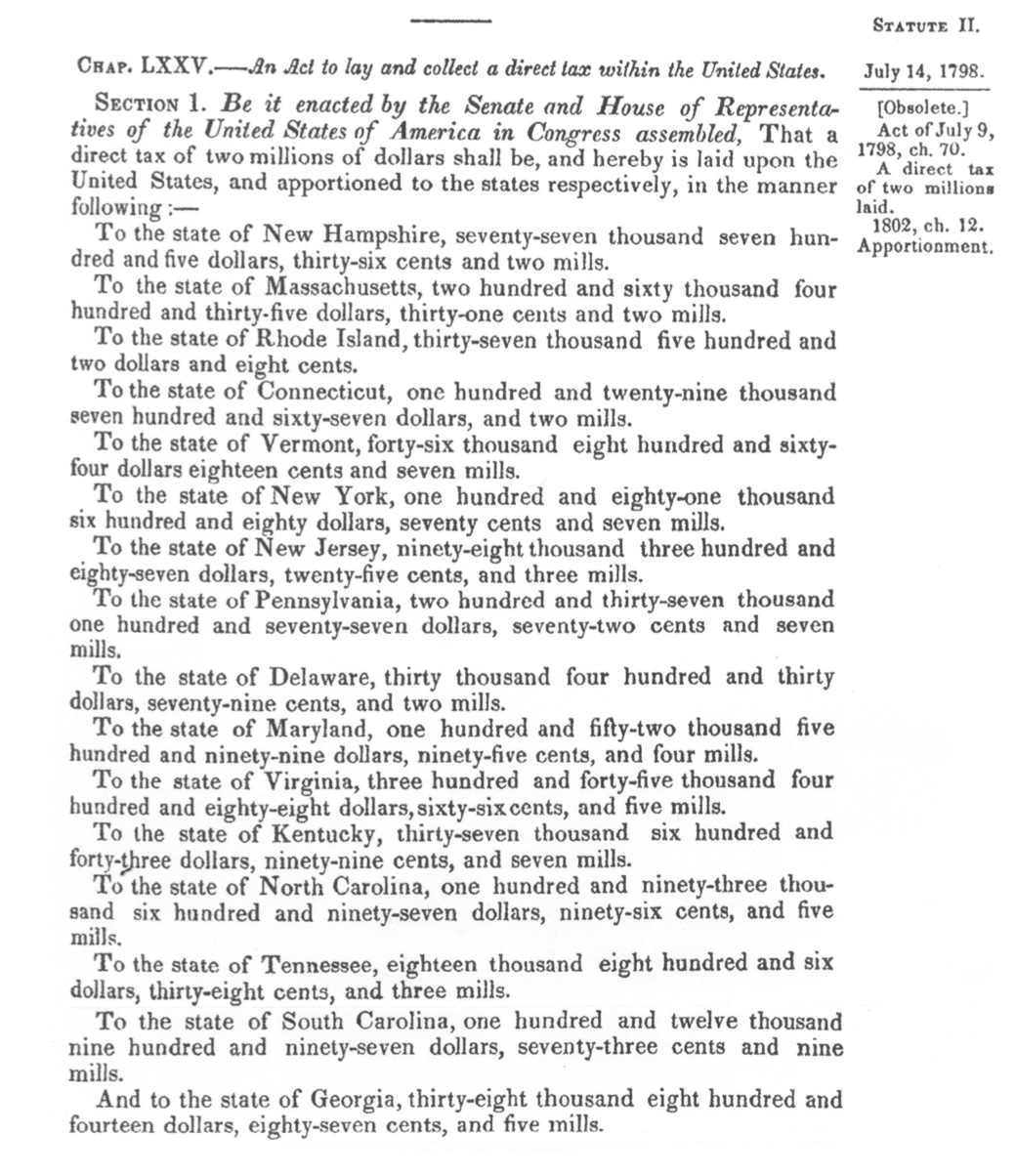

direct taxes - these are required to be “apportioned” and that means they are allocated to each of the fifty states based on the population of each state, and your individual tax bill is proportional to the population in your state

the “all other” category, a.k.a. not direct, a.k.a. indirect taxes - these are required to be “uniform” and that means that no matter in which of the fifty states you live, your tax liability would be the same

so if you are hit with an apportioned, direct tax, you would get a different tax bill based on the state in which you live, but your indirect tax bill would be the same regardless of the state in which you live.

there are no taxes that exist outside of these two categories.

there are no “schrödinger's cat” taxes that simultaneously exist in both of the direct and the not-direct categories.

every type of constitutional tax is either a direct tax, or it is an indirect tax. period.

the sixteenth amendment did not change anything about the categorization of taxes into the two distinct categories, nor did it change anything about the requirements for each of the two types of taxes.

See Moore v. United States, 602 U.S. ___ (2024)

… we begin with a brief review of Congress’s taxing power under the Constitution. … Article I of the Constitution affords Congress broad “Power To lay and collect Taxes, Duties, Imposts and Excises.” Art. I, §8, cl. 1. That power includes [in 2024 the U.S. Supreme Court is using the present tense “includes” so we can tell it is still the case post 16th amendment] “‘two great classes of’” taxes—direct taxes and indirect taxes. Brushaber v. Union Pacific R. Co., 240 U.S. 1, 13 (1916).

and

… Generally speaking, direct taxes are those taxes imposed on persons or property. See National Federation of Independent Business v. Sebelius, 567 U. S. 519, 570–571 (2012). As a practical matter, however, Congress has rarely enacted direct taxes because the Constitution requires that direct taxes be apportioned among the States. To be apportioned, direct taxes must be imposed “in Proportion to the Census of Enumeration.” U. S. Const., Art. I, §9, cl. 4; see also §2, cl. 3. In other words, direct taxes must be apportioned among the States according to each State’s population [in 2024 the U.S. Supreme Court is using the present tense “the Constitution requires,” “direct taxes must be imposed,” and “direct taxes must be apportioned” so we can tell it is still the case post 16th amendment]. … To state the obvious, that kind of complicated and politically unpalatable result has made direct taxes difficult to enact.

and

… By contrast, indirect taxes are the familiar federal taxes imposed on activities or transactions. That category of taxes includes duties, imposts, and excise taxes, as well as income taxes [income taxes are (present tense again) exclusively in the indirect class and therefore, being classed similarly with duties, imposts, and excise taxes, must share more characteristics in common with those taxes than they would with the taxes in the direct class]. U. S. Const., Art. I, §8, cl. 1; Amdt. 16. Under the Constitution, indirect taxes must “be uniform throughout the United States.” Art. I, §8, cl. 1. A “‘tax is uniform when it operates with the same force and effect in every place where the subject of it is found.’” United States v. Ptasynski, 462 U. S. 74, 82 (1983).

and

… the Sixteenth Amendment expressly confirmed what had been the understanding of the Constitution before Pollock: Taxes on income—including taxes on income from property—are indirect taxes that need not be apportioned [income taxes are (present tense again) exclusively in the indirect class, as they were understood to be even before Pollock]. Brushaber, 240 U. S., at 15, 18. Meanwhile, property taxes remain direct taxes that must be apportioned. See Helvering v. Independent Life Ins. Co., 292 U. S. 371, 378–379 (1934).

See Brushaber v. Union Pacific R. Co., 240 U.S. 1 (1916)

Again it has never moreover been questioned that the conceded complete and all- embracing taxing power was subject, so far as they were respectively applicable, to limitations resulting from the requirements of Art. I, § 8, cl. 1, that "all duties, imposts and excises shall be uniform throughout the United States," and to the limitations of Art. I, § 2, cl. 3, that "direct taxes shall be apportioned among the several States" and of Art. I, § 9, cl. 4, that "no capitation, or other direct, tax shall be laid, unless in proportion to the census or enumeration hereinbefore directed to be taken."

and

In fact the two great subdivisions embracing the complete and perfect delegation of the power to tax and the two correlated limitations as to such power were thus aptly stated by Mr. Chief Justice Fuller in Pollock v. Farmers' Loan Trust Company, supra, at page 557: "In the matter of taxation, the Constitution recognizes the two great classes of direct and indirect taxes, and lays down two rules by which their imposition must be governed, namely: The rule of apportionment as to direct taxes, and the rule of uniformity as to duties, imposts and excises."

and

It is to be observed, however, as long ago pointed out in Veazie Bank v. Fenno, 8 Wall. 533, 541, that the requirement of apportionment as to one of the great classes and of uniformity as to the other class were not so much a limitation upon the complete and all embracing authority to tax, but in their essence were simply regulations concerning the mode in which the plenary power was to be exerted.

and

In the whole history of the Government down to the time of the adoption of the Sixteenth Amendment, leaving aside some conjectures expressed of the possibility of a tax lying intermediate between the two great classes and embraced by neither, no question has been anywhere made as to the correctness of these propositions.

and

… the [appellant’s erroneous] contention that the [Sixteenth] Amendment treats a tax on income as a direct tax although it is relieved from apportionment and is necessarily therefore not subject to the rule of uniformity as such rule only applies to taxes which are not direct, thus destroying the two great classifications which have been recognized and enforced from the beginning [again, if the appellant’s "erroneous assumption” were true that the 16th amendment gave Congress the power to levy a new type of tax that was not subject to the requirements of either the direct class or the indirect class it would destroy the “two great classifications which have been recognized and enforced from the beginning”], …

and

… is also wholly without foundation [“wholly without foundation” means that the appellant’s assumption is entirely unsupported and therefore proven to be false] since the command of the Amendment that all income taxes shall not be subject to apportionment by a consideration of the sources from which the taxed income may be derived, forbids the application to such taxes of the rule applied in the Pollock Case [the command of the 16th amendment is that an indirect income tax can no longer be treated as a direct tax simply by looking at the source of the “income,” which is “the rule applied in the Pollock Case”] by which alone such taxes were removed from the great class of excises, duties and imposts subject to the rule of uniformity and were placed under the other or direct class [“the rule applied in the Pollock Case” was the only time income taxes were taken out of the indirect class and treated as if they were in the direct class].

and

This must be [“this must be” means that it must be true that the command of the 16th amendment is to make sure that indirect income taxes are never again treated as direct because of the source of “income”] unless it can be said that although the Constitution as a result of the [Sixteenth] Amendment in express terms excludes the criterion of source of income, that criterion yet remains [the “this must be” is not true if the source of income is allowed to be taken into account] for the purpose of destroying the classifications of the Constitution [which again would result in the destruction(!) of the classifications of direct and indirect] by taking an excise out of the class to which it belongs [the income tax is referred to here as an excise and therefore the class to which it belongs is the indirect class] and transferring it to a class in which it cannot be placed consistently with the requirements of the Constitution [an inherently excise-like income tax cannot be put into the direct tax class and be consistent with the requirements of the Constitution].

and

Indeed, from another point of view, the Amendment demonstrates that no such purpose was intended [obviously the intended purpose of the 16th amendment was to prohibit the placing of an inherently excise-like income tax into the direct tax class] and on the contrary shows that it was drawn with the object of maintaining the limitations of the Constitution and harmonizing their operation [obviously the intended purpose of the 16th amendment was to maintain the constitutional requirements of apportionment for direct taxes and uniformity for indirect taxes and to create harmony between them].

and

We say this because it is to be observed that although from the date of the Hylton Case because of statements made in the opinions in that case it had come to be accepted that direct taxes in the constitutional sense were confined to taxes levied directly on real estate because of its ownership, the Amendment contains nothing repudiating or challenging the ruling in the Pollock Case that the word direct had a broader significance [Pollock broadened what was considered to be a direct tax and there is nothing in the 16th amendment that states that the broader meaning in Pollock is no longer applicable] since it embraced also taxes levied directly on personal property because of its ownership, …

and

… and therefore the Amendment at least impliedly makes such wider significance a part of the Constitution — a condition which clearly demonstrates that the purpose was not to change the existing interpretation except to the extent necessary to accomplish the result intended [it is also obvious that the 16th amendment was limited to changing only what it expressly states], that is, the prevention of the resort to the sources from which a taxed income was derived in order to cause a direct tax on the income to be a direct tax on the source itself and thereby to take an income tax out of the class of excises, duties and imposts and place it in the class of direct taxes [the 16th amendment’s only change was that the source of the “income” could no longer be the reason for taking an inherently excise-like income tax out of the indirect class and putting it in the direct class].

See Pollock v. Farmers' Loan & Trust Co., 157 U.S. 429 (1895)

And although there have been, from time to time, intimations that there might be some tax which was not a direct tax, nor included under the words 'duties, imports, and excises,' such a tax, for more than 100 years of national existence, has as yet remained undiscovered, notwithstanding the stress of particular circumstances has invited thorough investigation into sources of revenue [there are no hybrid taxes or taxes that are not in one of the two classes].

and

From these references—and they might be extended indefinitely it is clear that the rule to govern each of the great classes into which taxes were divided was prescribed in view of the commonly accepted distinction between them and of the taxes directly levied under the systems of the states; and that the difference between direct and indirect taxation was fully appreciated is supported by the congressional debates after the government was organized [it is clear that the apportionment rule for direct taxes and the uniformity rule for indirect taxes were determined based on the commonly accepted distinctions between the two classes, which the congressional debates show was fully appreciated by the Framers of the U.S. Constitution].

again, the fact that i had to put this very basic understanding into a court filing so that the judge and the attorneys for the irs could read it should tell you how this is going.

next up: more on the “commonly accepted distinctions between the two classes, which the congressional debates show was fully appreciated by the framers of the u.s. constitution.”